At an age when most kids around the world are learning to read, write and learn their times tables, seven-year-old Omony Geoffrey was learning a much different lesson. One day in 1995, he was kidnapped from his small village in northern Uganda and forced to become a child soldier with the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a rebel group in Northern Uganda responsible for countless human rights violations and acts of violence since 1989. He spent a year in captivity until his group of militants was ambushed by the national army. During the crossfire, Geoffrey hid in a banana plantation until the gunshots finally ceased the next morning. That morning, he found a man nearby, told him about his situation, and eventually made his way back to his community.

“I wasn’t reintegrated back into the community as much as dumped back into it,” Geoffrey, now 29, says. Finding a way to pay school fees and to earn money for food was hard enough for most young people in Uganda, but even more so for a former militant. As a way to combat the isolation he felt, Geoffrey started a youth group to bring ex-combatants together and help connect them to resources.

One of the men Geoffrey met was Okello Charles, who was also abducted by the LRA. At the age of nine, Charles was appointed the chief personal escort of LRA leader Joseph Kony. Two and a half years went by before Charles was able to escape, but his trouble didn’t end there. Once he was back home, he wasn’t able to access land, and felt stigmatized and voiceless.

‘“The local community views us as the source of their problem, yet we were also abducted,” Charles said in a 2013 interview. ‘We live in fear because we are aware that people resent us.’

He realized this experience was not unique among former child soldiers, and wanted to take action to provide community and solidarity.

Today, both Geoffrey and Charles work at Youth Leaders for Restoration and Development (YOLRED), an organisation helping other former child soldiers to recover from trauma, develop job skills, and advocate for human rights, land rights and justice in their communities. As the only community organization in Uganda designed, built and run by former child soldiers, YOLRED’s mission is to ‘transform our communities by promoting peace, unity and fairness for everyone in Northern Uganda.’

There is a tremendous need for YOLRED’s work. After conflict, reconciling a community is no simple process. Civilians are made to live next door to the soldiers who may have harassed and terrorized them, and are expected to move forward without apology or justice. The former child soldiers, meanwhile, are suddenly thrust into the world with no formal education, job training or land access, and face immense stigma. How can these fractured relations be mended, much less rebuilt?

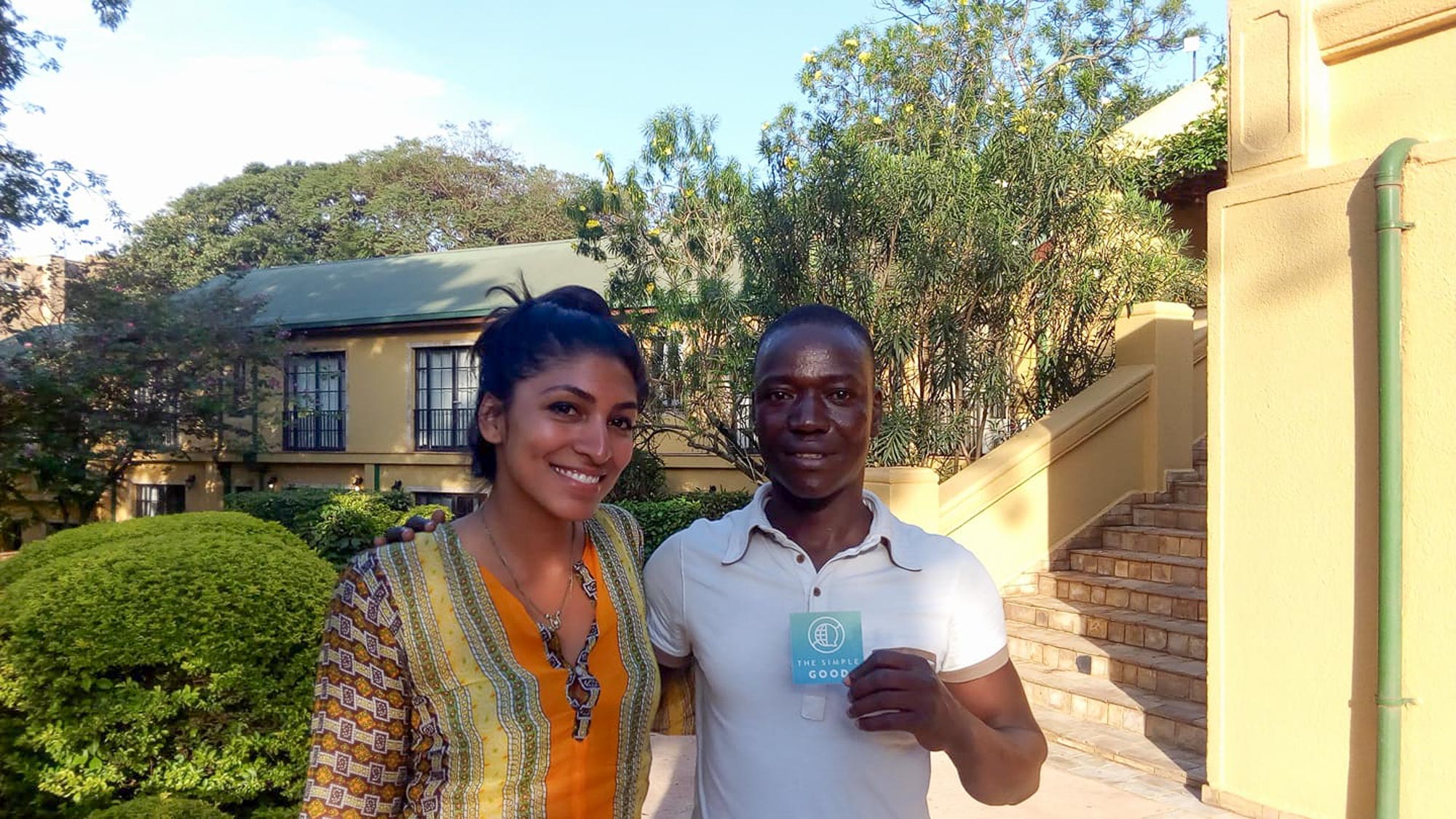

Like Geoffrey and Okello, Priya Shah, founder of community art non-profit The Simple Good (TSG), is one of those helping to mend relationships among at-risk youth in East Africa. Shah was raised in Chicago, but her mother grew up in Uganda. She believes that artistic expression can go a long way in bridging these divides.

“Many who have suffered from violence or trauma feel stigmatized, which can prevent youth from expressing themselves, let alone empowering themselves to open up,” she says. “Using the understanding that good that exists within all of us, and using the platform of art to express that, not only provides healing for our youth but an ability to pass on their stories to a larger audience, which allows us to heal each other.”

Priya’s work with The Simple Good brought her to Rwanda, where TSG collaborated with nonprofit organization Heart of a Thousand Hills to build a school in 2016 in Rwesero, in the country’s north east. This year, they returned to promote art and education at Golden Drop School and to host a cross-cultural exchange between Chicago & Rwandan artists at the Building Hope Art Exhibition.

Before heading back to Chicago, Priya decided to spend a few days in Uganda, where her mother grew up. Once dictator Idi Amin took power, in 1971, all Asians were forced to leave the country within 90 days, leaving everything they owned behind. Her family became refugees for a time, and had to quickly figure out where in the world to resettle. Priya is the first in her family to return. She visited her mother’s hometown of Masaka, including the street her mother once lived on. “It was surreal,” she says, to see first-hand the place her mother’s family had been driven from against their will.

After Priya was connected to Geoffrey through a mutual friend, he traveled over five hours to speak with her. “I think I will use The Simple Good’s [approach] as a strategy to affect the reintegration of the entire community of Northern Uganda…” he told her. “Especially the formerly abducted child soldiers.”

Not everyone is as receptive to arts programs as Geoffrey. When asked about the biggest challenges she faces in her work, Priya says, “Our largest challenge in bringing the arts to different communities is proving how art influences the soul and our ability to heal and overcome trauma in our lives. Another challenge is understanding [that] everyone is an artist, and there is no wrong way to create! I like to tell everyone that to be an artist is not about how 'good' you are but more so having the courage to create—and through that, you tell the world a story. By practicing that, we can see how everyone truly is an artist.”

The TSG’s work bringing out the universality of the artistic spirit can be seen in the organization’s Photo Blog, where partners around the world are encouraged to submit pictures that capture their personal vision of “the simple good.” The photos are then used in TSG’s classroom curriculums, inspiring young people to search for and express “the simple good” in their own life. “We have received over 1000 photos now and each photo is used as a teaching tool,” Priya says.

As for Geoffrey, he looks forward to bringing TSG’s approach to the former child soldiers in his community. “I think The Simple Good will do simple good for them,” he says.